You Might Be Wrong!

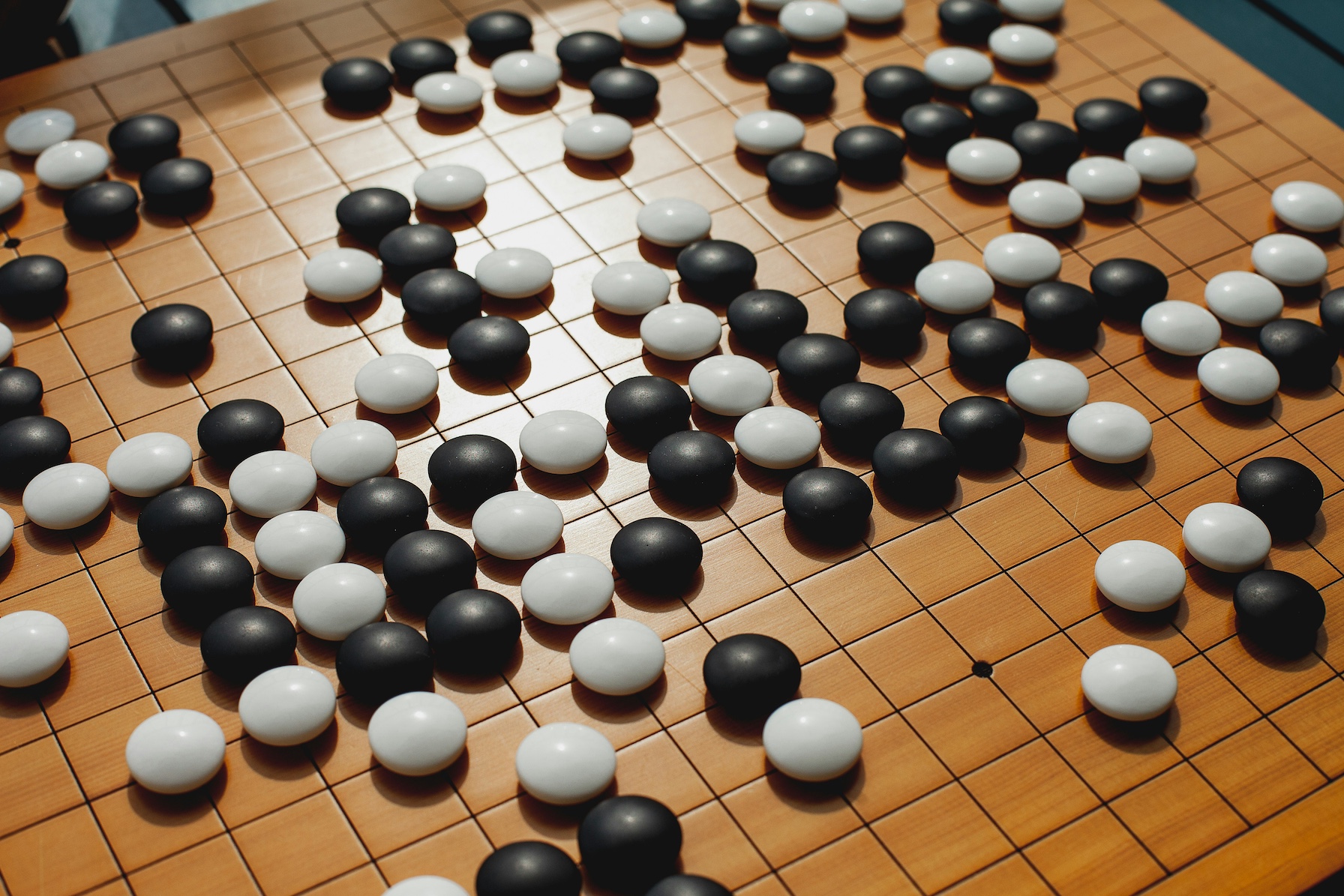

I recently came across the documentary AlphaGo - The Movie while reading The Coming Wave by Mustafa Suleyman, one of the founders of AI company DeepMind. In it, you can see how DeepMind’s computer program—named after the traditional board game Go—plays against Go world champion, Lee Sedol. In a series of five matches, Sedol loses 1–4.

Before the first match, Sedol predicted that he’d have a chance to win 5-0. Given his career success, he was so confident that he thought a machine would be no serious opponent. His human bias initially protected him from imagining a potential humiliation. During the match, though, you can clearly see how reality wreaks havoc on him and his emotions.

Human biases

Biases are shortcuts that help us survive and act quickly. They shape how we interact with others—whether it's a machine outsmarting us, a colleague trying to push for organisational change, or a random stranger asking us a favour.

There are many more biases in the world than I had imagined, as I recently found out through Rolf Dobelli’s book The Art Of Thinking Clearly: authority bias, outcome bias, association bias, and contagion bias, to name just a few.

As they reinforce what I saw in the AlphaGo documentary, I’ll share a few that I found particularly striking:

The Overconfidence Effect

The one that Lee Sedol probably fell victim to is the Overconfidence Effect. He is far from the only one to fall victim to this effect: in a popular study, 70-90 percent of Americans consider themselves to be above-average drivers, even though mathematically speaking, only 50 percent can be above the average.

As Dobelli quotes one of the researchers, “we systematically overestimate our knowledge and our ability to predict—on a massive scale”. The overconfidence effect “measures the difference between what people actually know and how much they think they know.”

What struck me is that experts can be equally prone to this effect as people unfamiliar with a given field. Lee Sedol, as a Go expert, is a prime example.

Social Proof

Another fascinating bias is Social Proof. It describes the phenomenon of people considering something to be true the more often they hear about it.

One popular example from another great book, Yuval Noah Harari’s Nexus, is the witch hunts of the early modern period (1450-1750). Without evidence, people—mostly women—were sentenced to death because someone spread the rumour that they were involved in witchcraft.

According to the Encyclopedia Britannica, "Witchcraft [...] exists more in the imagination", but it "has constituted for many cultures a viable explanation of evil in the world". The more people shared lies, the more they believed them to be true and took them for granted. A rumour turned into truth through mere gossip!

Now compare the speed at which misinformation spread in the 16th century to that of the modern world.

The Sleeper Effect

Propaganda works in a very similar way, as Dobelli describes in another chapter, where he explains the so-called Sleeper Effect. According to a famous study, it occurs when soldiers who are exposed to war propaganda clearly identify the material as “manipulative” whereas weeks later, they could only recall that “war is good” but weren’t able to remember the manipulative purpose of the movies they had been exposed to.

When a topic strikes a chord with us, even though it is apparently wrong, the “influence will only increase over time”. Why, Dobelli asks, and the best explanation we seem to have to date is that “the source of the argument fades faster than the argument” itself.

That may explain why people exposed to flat earth theories actually believe in such far-fetched ideas, no matter whether the source is reliable or not.

Truth seeking

So how do we avoid our own bias, which apparently is capable of manipulating our perception of truth so profoundly?

There’s a famous anecdote of Jeff Bezos where Amazon’s Head of Customer Service defended a metric saying that customers waited less than sixty seconds when calling customer service. As this conflicted with customer complaints, Jeff picked up the phone himself and dialed Amazon’s customer service number. Everyone in the meeting ended up waiting more than ten minutes before anyone answered.

Being able to expose a truth undeniably is very satisfying! In many cases, though, since the world is complex beyond our understanding, there are often only approximations of the truth.

I do believe, though, that as responsible citizens, we should always make an effort to seek the truth, using the multitude of tools at our disposal to get closer to it.

Here are some ideas that help drill down into the facts.

Fact checking

Even in Dobelli’s book, some citations are difficult to verify. Robust evidence should be supported by studies with a high number of randomized participants, which are peer-reviewed and published in reputable journals. All too often, this is not the case.

Instead of verifying all the news ourselves, fact-checking networks are a great shortcut. They conduct thorough research to verify information shared on news sites and social media and help uncover the most common pieces of misinformation. One of my favourite ones is Correctiv (German), which sends daily updates on the latest “fake news” via WhatsApp.

I also find government-funded, non-profit organisations a lot more trustworthy than self-acclaimed experts on YouTube or TikTok sharing their theories. Ever since I watched the Netflix documentary The Social Dilemma and saw how internet algorithms influence people and society, I’ve tried to abstain from social media as much as possible.

Using LLMs

Another way to drill into the facts quickly is LLMs. Nowadays, we have a bulk of humanity’s information legacy available at our fingertips through a single prompt; it is relatively easy to run an LLM against your hypothesis and deliberately ask it to criticize your thoughts or ideas.

We should keep in mind, though, that LLMs are usually very supportive of our queries, and that some might be less ethically trained than others. Ideally, run your prompt against multiple LLMs and compare the results.

Also, hallucinations can be highly misleading, which is why fact-checking tools for AI exist. You can also directly use LLMs that are based on scholarly resources, such as consensus.app or elicit.com.

Awareness

Last but not least, I find it easy to overreact to information that doesn’t fit our view of the world. I usually try to avoid or at least delay instant (and often biased!) judgement but in the end, I’m as prone to manipulation as everyone else is!

Admitting mistakes or being proven wrong, however, is emotionally difficult for many people, including myself. Throughout our lives, many of us have built sophisticated response mechanisms to help protect us from discomfort. Many of those mechanisms are still alive and unaddressed throughout our adult lives, and only a skilled therapist may be able to uncover their root cause.

There’s no single piece of advice to help address this issue quickly, but mindfulness has been a great way—for me at least—to become more aware of negative emotions and deal with them more skillfully.

Can technology save us?

In one of the last chapters of his book, Rolf Dobelli talks about a bias called The Illusion of Attention, a phenomenon observed by researcher Daniel Simons. In it, he led an experiment called the Selective Attention Test in which the viewer’s task is to count the number of passes between basketball players in white shirts. Being so focused on the challenge, the viewer barely notices a person in a gorilla costume walking past the screen.

As Dobelli says: “...such gorillas stomp right in front of us—and we barely spot them”. It’s the same method of misdirection that magicians use when they make a rabbit appear from thin air.

What’s clear to me from all these anecdotes, from witch hunts to YouTube propaganda to stomping gorillas: our cognitive biases can leave us blind and naive in hindsight, similar to how Lee Sedol underestimated his artificial opponent. It's only human after all!

In the end, I guess, only time will tell whether artificial intelligence can save us from our naivety, or whether it will make our illusions even harder to escape...

Resources from this blog post

- List of Cognitive Biases on Wikipedia

- Fact-checking networks on Wikipedia

- The Art Of Thinking Clearly by Rolf Dobelli

- Nexus by Yuval Noah Harari

- The Coming Wave by Mustafa Suleyman

- AlphaGo - The Movie on YouTube

- The Social Dilemma on Netflix

- Fact-checking tools for AI on ijnet.org