Breaking out of the monolith with Module Federation

Moving from a monolith to a modular architecture: a worthwhile effort? — Photo by Nano Banana

Rapid feature development is a double-edged sword. For startups, moving fast and scaling quickly usually means outgrowing your architecture quickly.

If your build times are longer than your lunch breaks or shipping a simple tweak feels like performing open-heart surgery, you’ve probably hit the wall of scale.

Let's talk about a better way forward. We’re diving into the front-end stack today to see how Module Federation can help restore development velocity.

The Burden of the Unmaintained Monolith

Working within an unmaintained codebase is a heavy burden for any engineering team. In my experience, large codebases that lack architectural governance and engineering rigor eventually display the same symptoms:

- 🌪 Inconsistent patterns emerge: Without a shared standard, every developer builds differently. Bad practices spread unnoticed, technical debt leads to ever more bloat.

- 🧩 Architectural chaos unfolds: With no consistency, the code base becomes harder to understand, and tight coupling turns simple changes into monumental risks.

- 🕰 The stack deteriorates: Tooling becomes a liability rather than an asset. Upgrades become expensive and risky, leaving the team trapped with outdated dependencies.

Unfortunately, this doesn't just affect engineers—it ultimately affects users as well:

- 💣 Instability: Flaky, slow test suites lead to "crossing your fingers" during a release, inevitably resulting in a glitchy user experience.

- 📉 Performance: Without clear ownership of global performance metrics, your app becomes sluggish over time.

- 🐛 Bugs: Critical bug fixes that should take minutes end up taking days to navigate the release pipeline.

In short: Your front-end architecture has become a bottleneck for the entire organization.

A Path Toward Autonomy

I wouldn't be writing this if I hadn't been trapped in an unmaintainable monolith myself. I’ve explored various escape routes—from modular SPAs and Multi-Page Apps (MPAs) to the more extreme approach of embedding modules via iFrames.

While the "best" strategy depends on your specific use case, one approach that worked particularly well for me is Micro-Frontends with Module Federation. It unlocks two critical capabilities:

- Isolated Development: The ability to build and spin up features in fresh, independent environments.

- Seamless Integration: Hooking those features back into the "host" app without the user noticing.

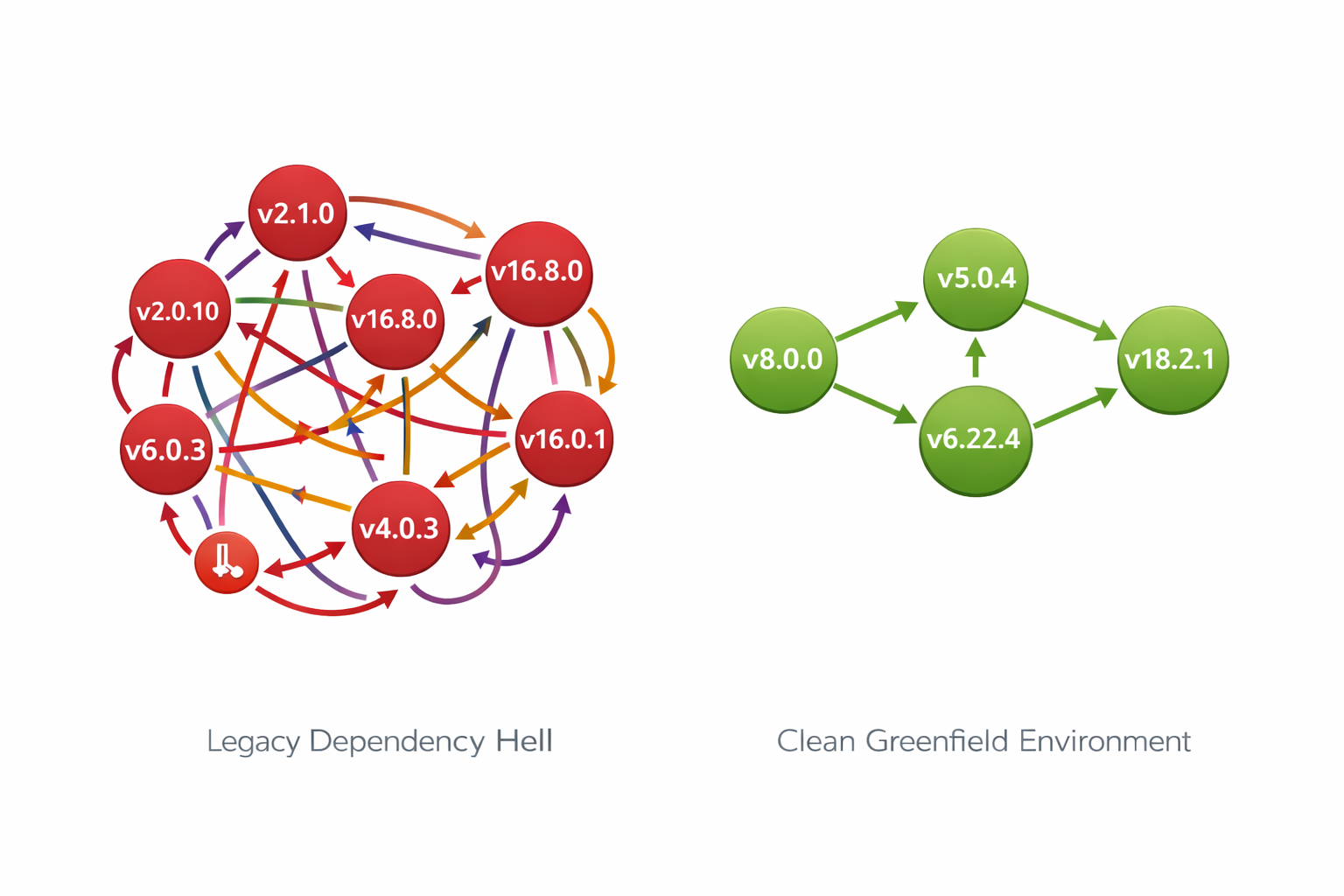

Working in a completely isolated environment—where the tech stack is unconstrained and the integration is invisible to the user—is a win-win. From a developer’s perspective, this isolation provides:

- 🧠 Cognitive Ease: You work within a smaller repository, focusing only on the code that matters.

- 📦 Reduced Blast Radius: Clearly bounded contexts ensure that a failure in one feature doesn't bring down the entire platform.

- ✂️ Leaner Dependencies: You can tailor dependencies to the specific feature rather than inheriting the entire monolith's baggage.

- ⛵️ Rapid Pipelines: CI/CD (specifically static analysis and testing) runs in a fraction of the time.

- ⚡️ Faster Resolution: Issues have a smaller surface area, making them significantly easier to debug and fix.

The most immediate benefit, however, is the psychological shift. You are no longer fighting heavily coupled legacy system; you are building in a fresh, greenfield environment.

It's easy to get stuck in dependency hell when complexity increases — Photo generated by DALL-E

The "Magic" of Module Federation

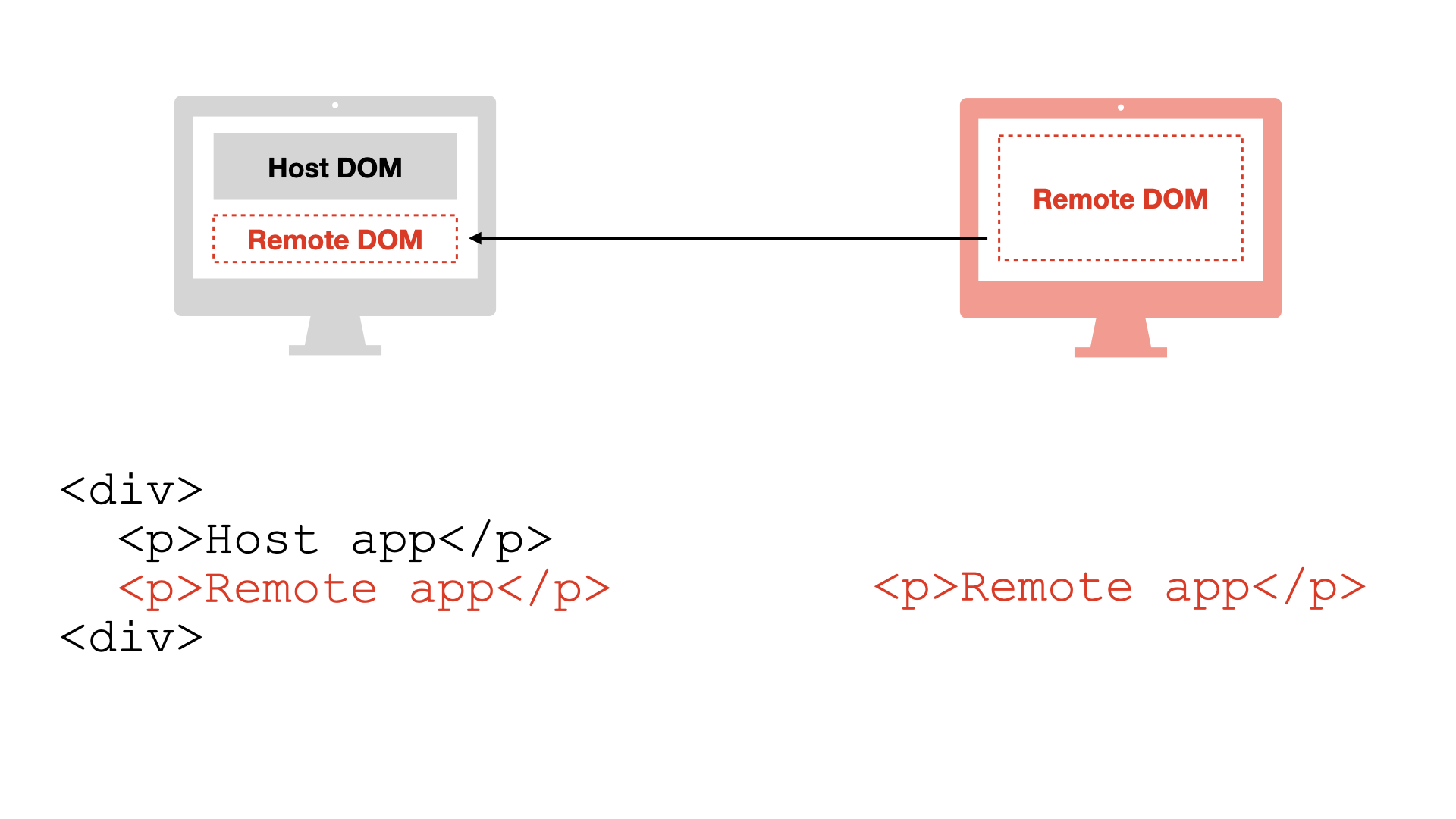

This sounds complicated at first, but it’s actually a simple, elegant technology called Module Federation. It allows two fully isolated codebases to be seamlessly stitched together into a single, coherent user experience.

In a nutshell, Module Federation enables you to:

- Launch Greenfields: Spin up a new app in a fresh repository with its own independent pipeline.

- Bridge the Gap: Seamlessly hook the new app's DOM tree into any entry point within your legacy host.

- Dual-Mode Execution: Run each remote module in total isolation (standalone mode) or embedded within the host.

Same context, different repositories

Crucially, the remote app runs in the same execution context as the host. This means it isn't sandboxed like an iFrame; it has access to the host's scope, allowing for shared dependencies and high-performance communication. It also means your remote app is inheriting the host app's CSS (more on that later).

From a development perspective, this is an opportunity to adopt a modern stack—like moving to TypeScript—even if your host app is stuck in the past. You could even technically run a React micro-frontend inside a Vue host, though Module Federation authors themselves warn against "framework anarchy" for the sake of better developer experience. As always: with great freedom comes great responsibility.

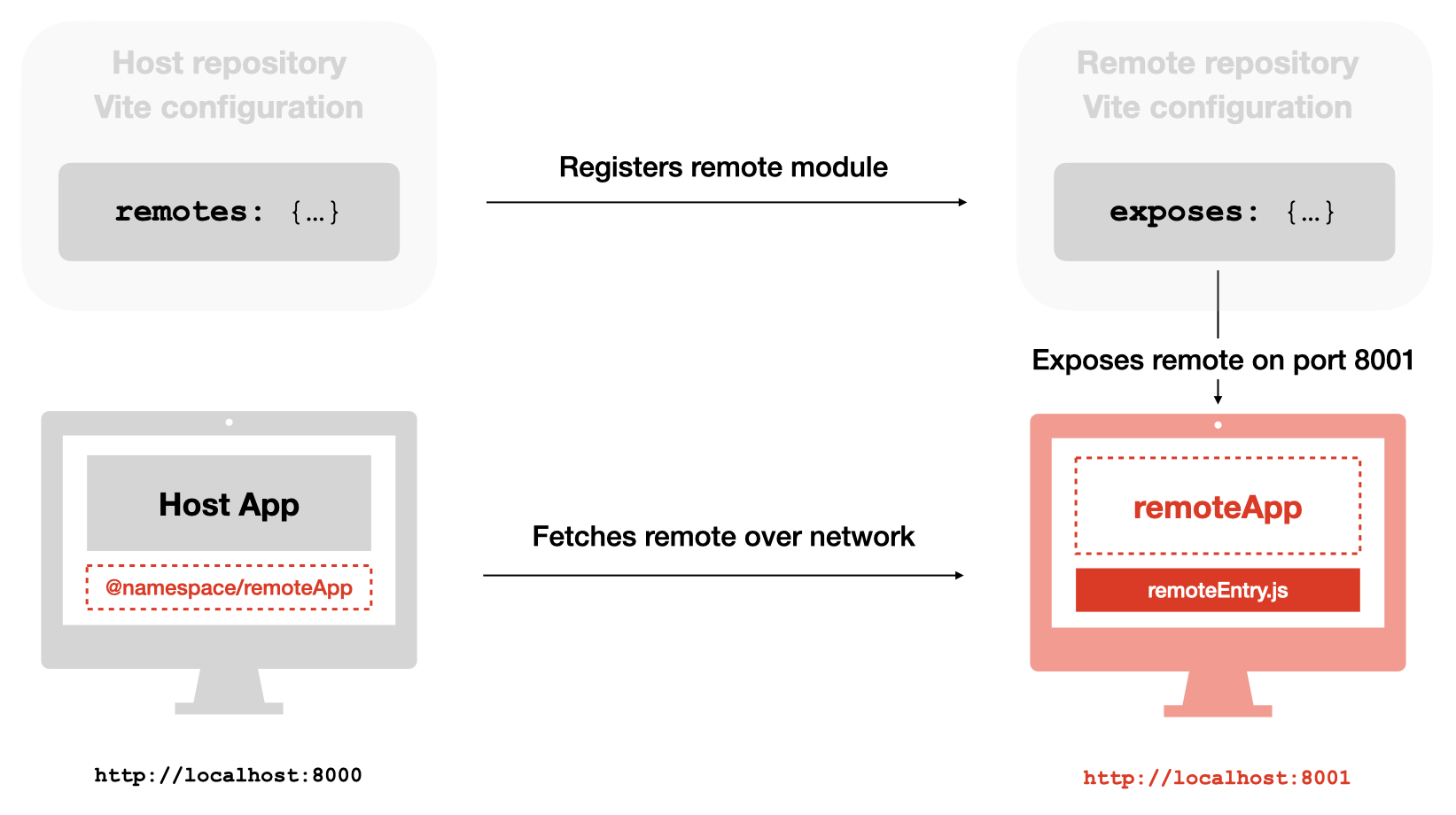

Let's take a look at the high-level picture:

Find concrete examples for React, Vue and other UI libraries in the working implementations section of Module Federation's Vite repository.

💡 Build time vs. runtime federation

By default, many setups register the link to the remote module at build time, meaning the host knows exactly where to look before it ever hits the browser. However, you can also configure it at runtime using the corresponding plugin, allowing the browser to resolve modules dynamically on the fly.

Configuring Module Federation with Vite

Next, I'm going to walk you through the remote and host setup for a React app. If you're already familiar with this part or not interested in implementation details, you may want to skip to one of the following sections:

Setting up the Remote App

First, we configure the remote—the standalone feature that will be "plugged into" the host. At a minimum, you must define a name for the module, the specific component to expose, and the filename that will serve as the entry point. This will be served from the port defined in your Vite configuration.

// vite.config.js (Remote App)

export default defineConfig({

server: {

port: 8001,

origin: 'http://localhost:8001',

},

plugins: [

federation({

name: 'remote_app', // Unique name for the remote

filename: 'remoteEntry.js',

// Define which components to expose to the host

exposes: {

'./App': './src/App.jsx',

},

shared: ['react', 'react-dom'], // Share core libraries to avoid bloat

}),

],

})

Note: App.jsx can be any React component, from a single button to a complex multi-page sub-application. I'll also talk about the aspect of routing in remote modules further down.

Setting up the Host App

With the remote configured, we can now register it in the host. Ensure the URL, port, and filename exactly match the remote's output.

// vite.config.js (Host App)

export default defineConfig({

plugins: [

federation({

name: 'host_app',

remotes: {

// The key '@remote' is the alias you'll use in your imports

'@remote': 'http://localhost:8001/assets/remoteEntry.js',

},

shared: ['react', 'react-dom'],

}),

],

})

The host app is now "aware" of the remote module and is ready to fetch it over the network.

Note: For production environments, the remote URLs should be controlled by environment variables and be configured accordingly in your deployment pipeline.

Integrating the Remote into the Host

Once registered, importing the remote module feels just like importing a local component. You can drop it anywhere in your component tree.

// here, `@remote` is our namespace, `App` the exposed module to import

import RemoteApp from '@remote/App'

export default function App() {

return (

<div className="container">

<h1>Host Application</h1>

<RemoteApp />

</div>

)

}

Handling Network Resilience

You might wonder: What happens if the network fails or the remote server is down? Since Module Federation fetches code over the wire at runtime, you must account for loading states and potential failures to prevent your entire host app from crashing.

In a production environment, you should use Asynchronous Imports combined with React’s Suspense and Error Boundaries. This ensures that if the remote fails to load, the rest of your application remains functional.

import React, { Suspense } from 'react'

// Lazily load the remote component

const RemoteApp = React.lazy(() => import('@remote/App'))

export default function App() {

return (

<div className="host-container">

<ErrorBoundary fallback={<p>Feature temporarily unavailable.</p>}>

<Suspense fallback={<p>Loading remote feature...</p>}>

<RemoteApp />

</Suspense>

</ErrorBoundary>

</div>

)

}

Advanced configuration options

This basic setup gets you up and running quickly, but real-world production apps require some more advanced techniques. Here are three of the most common ones I've encountered and how to clear them.

1. Managing Shared Dependencies

Unless you’re opting for "Micro-Frontend Anarchy," you’ll want to share core libraries like react-dom between your host and remotes. This serves two purposes:

- Performance: It prevents the browser from downloading the same library multiple times.

- Stability: It prevents version conflicts that occur when two different versions of a package try to co-exist in the same app.

// vite.config.js

export default defineConfig({

plugins: [

federation({

name: 'host', // or 'remote'

// Share core dependencies to ensure singleton behavior

shared: ['react', 'react-dom', 'react-router-dom'],

}),

],

})

Note: Ensure this configuration exists in both the host and the remote. For advanced needs like tree-shaking or eager loading, check the official Shared documentation.

2. Sharing Data Across Boundaries

One of the most elegant aspects of Module Federation is that the "boundary" between apps is just a standard component interface. Passing data is as simple as passing props:

// In the Host App

<RemoteApp user={{ name: 'Marcel' }} onTrackEvent={handleTrackEvent} />

This works exactly as if the component were local. Beyond primitives and objects, I recommend limiting this interface to just the minimum amount of data that is required and for cross-cutting concerns—like tracking or analytics—rather than domain logic. By keeping business logic internal, you maintain true encapsulation.

export default ({ user, onTrackEvent }) => {

const onClick = () => onTrackEvent('track button click')

return

<button onClick={onClick}>

{{user.name}}

</button>

}

This explicit interface is one of my favourite parts of Module Federation as it essentially serves as an explicit contract, forcing you to define exactly what data is allowed to cross the boundary between your bounded contexts.

3. Seamless Routing

How do you handle a remote app that has multiple pages of its own? The most common pattern is to "delegate" a sub-path to the remote module (e.g., yourapp.com/settings/*).

Host Configuration

The host defines a "wildcard" route that hands over control to the remote component.

// Host Router

<BrowserRouter>

<Routes>

<Route path="/" element={<Home />} />

{/* The '/*' allows the remote to handle its own sub-routes */}

<Route path="/settings/*" element={<RemoteSettingsApp />} />

</Routes>

</BrowserRouter>

Remote Configuration

The remote then defines its internal routes relative to that base path.

// Remote App (RemoteSettingsApp)

export default function RemoteRouter() {

return (

<Routes>

<Route path="/" element={<GeneralSettings />} />

<Route path="security" element={<SecuritySettings />} />

</Routes>

)

}

With this setup:

/settingsrendersGeneralSettings./settings/securityrendersSecuritySettings.

Tip: Remember to include your routing library (like react-router-dom) in your shared dependencies to ensure the host and remote are using the same history instance.

The Trade-offs

With all this architectural "marvel," you can probably smell the complexity from a mile away. Module Federation helps you break out of the monolith, but it introduces a few challenges of its own.

How to slice your app

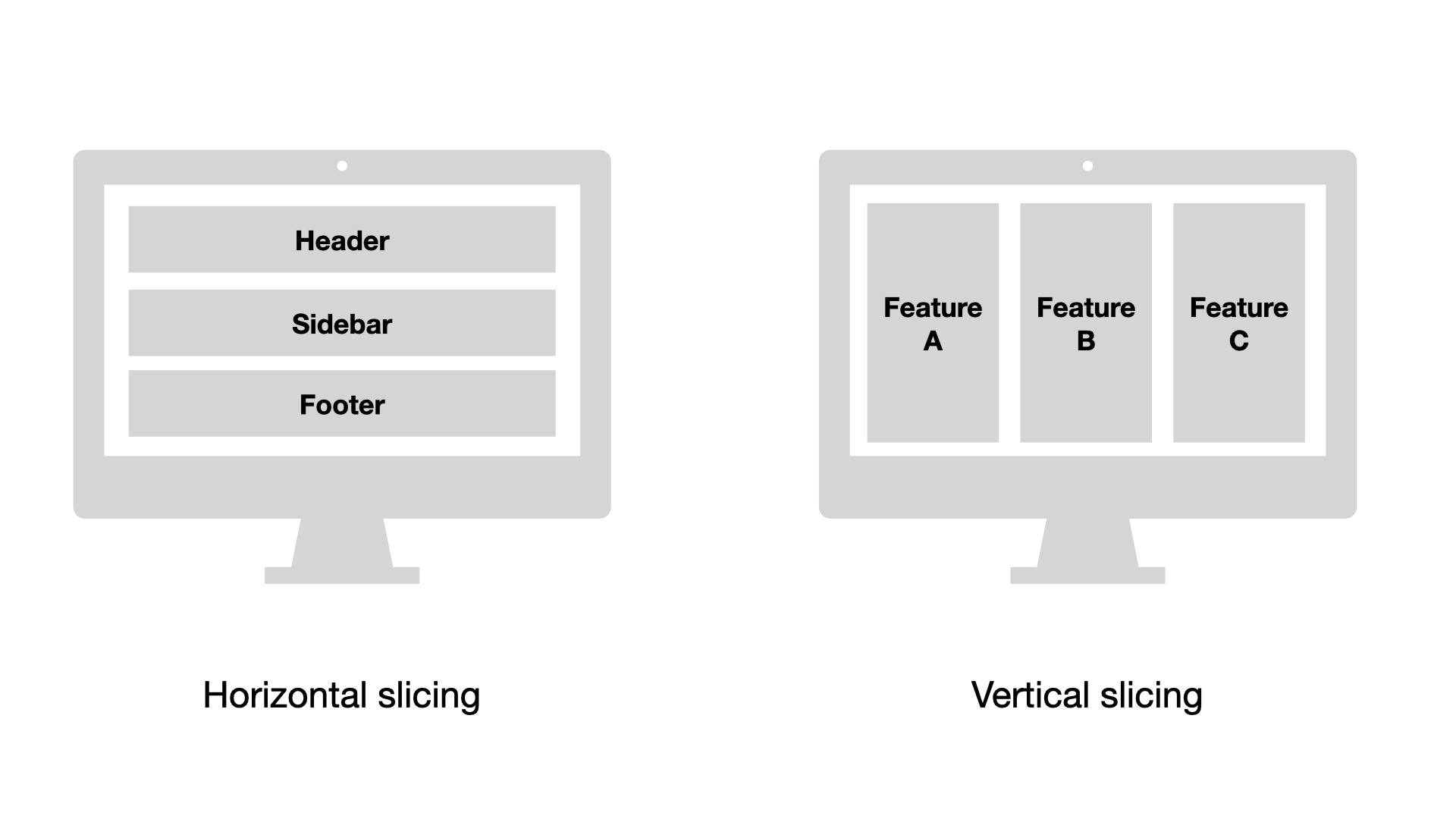

One of the first—and most difficult—questions you’ll face is how to actually partition your application. There are two primary schools of thought here:

- Horizontal Slicing: You split the app by technical or visual layers. For example, the Header, Sidebar, and Footer each become their own Micro-Frontend.

- Vertical Slicing: You divide the app by business domain. Each Micro-Frontend becomes a standalone feature—like "User Settings," "Checkout," or "Analytics Dashboard."

Two approaches to slicing your monolith into smaller modules

In my experience, Vertical Slicing is the superior strategy. When you slice vertically, you create self-contained modules that represent a coherent unit. These modules can be run, developed, and tested in total isolation. Conversely, splitting the app horizontally rarely offers much benefit as it doesn't give the developer any real autonomy because these components, e.g. a sidebar, usually can't "do" anything without the rest of the page.

From a user and testing perspective, each Micro-Frontend should encapsulate a complete user journey. This allows you to perform meaningful end-to-end testing on the module itself, ensuring that a "feature" works before it ever meets the host.

The Boilerplate Tax

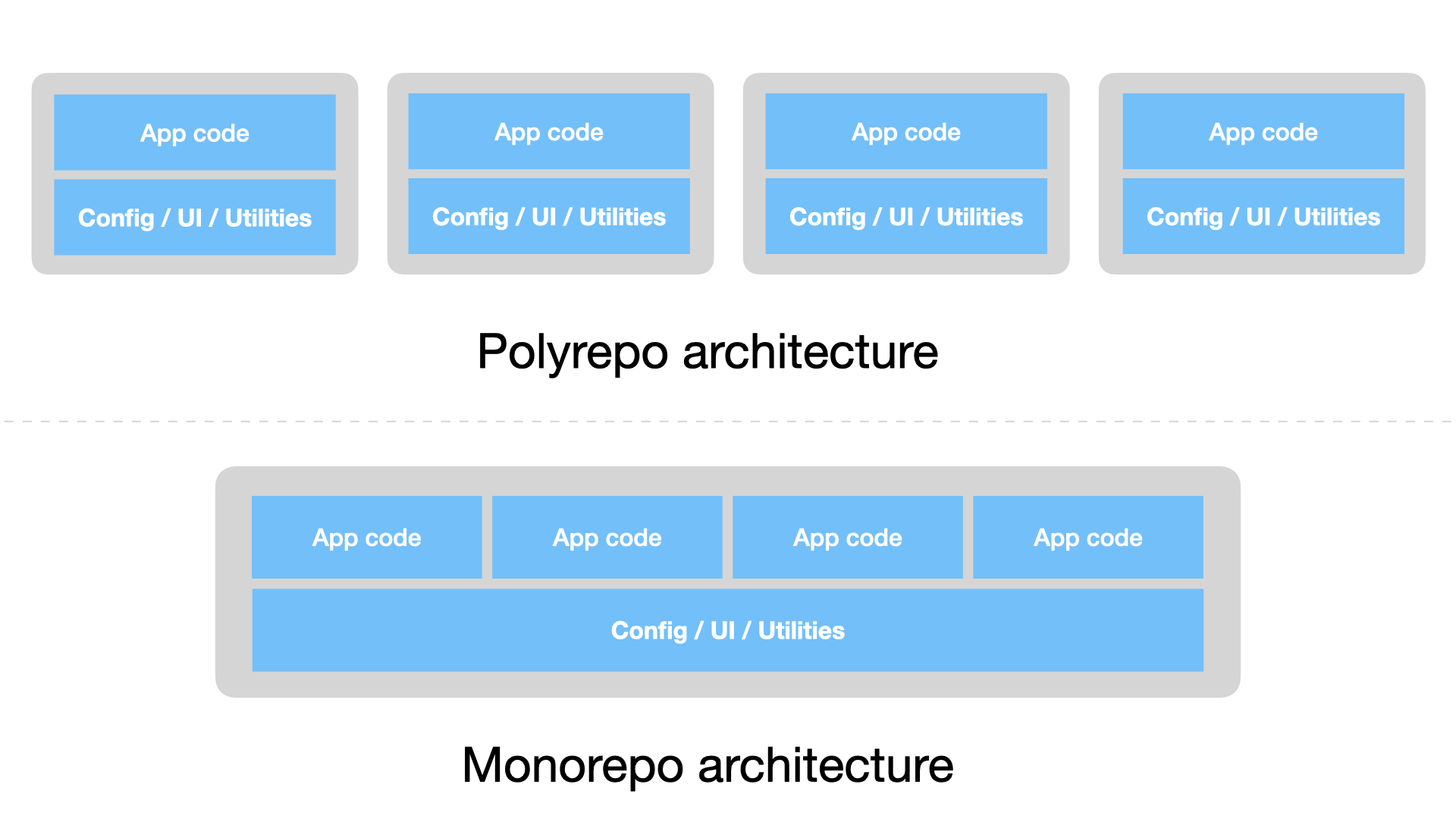

As soon as you spin up your second or third micro-frontend, the "greenfield" excitement wears off and you're left with a mountain of mundane configuration. You’ll find yourself duplicating things like:

- TypeScript and ESLint rules

- Vite and Testing configurations

- CI/CD pipeline logic

If you stay in a polyrepo (separate repositories), this boilerplate will eventually suffocate your productivity due to the substantial maintenance overhead. The only sensible way to scale this is to move toward a monorepo (using tools like Nx or Turborepo). This allows you to share build logic and linting rules across all modules while keeping them independently deployable.

Check out the Module Federation Monorepos docs for a deep dive on this approach.

Dependency sharing

Sharing a UI library or utility package sounds easy until you actually do it. If a shared library is currently trapped inside your monolith, you’ll have to perform "architectural surgery" to pull it out into its own package, then bundle, version and distribute it to each of your federated modules.

This is where teams may struggle: a shared library adds a critical layer of friction to your team's flow. Each update to the package requires an update to two or more different repositories, and teams must wait for the registry to be updated before they can see the impact of their changes.

Again, a monorepo is an elegant way out of this; it allows you to make a change to a shared library and see the impact on your federated modules instantly, without waiting for a private NPM registry to update.

Style isolation

When you stitch two separate apps together, their global CSS scopes collide. To prevent your UI from turning into a battleground, the Module Federation docs actually include a whole page on style isolation.

While the docs suggest techniques like BEM or scoped styles, I find that you should ideally isolate style scopes as much as possible, while importing common components from a shared UI library, wrapping not only the components themselves but also your organisation's custom theme.

For instance, using Tailwind CSS allows you to base everything on a common utility library, while global theming can either be duplicated across repositories, as a deliberate trade-off. Or you wrap it in a package serving as the single source of truth, so style drift becomes less of an issue.

The "Silent Failure" Risk

In a monolith, a missing function may cause a build error. In Module Federation, however, a missing remote module or a version mismatch happens at runtime.

You cannot rely on the compiler to save you anymore. You must invest in Integration Testing (like Playwright or Cypress) that runs against the host and remotes together. Without automated end-to-end checks, you’re just hoping that the "bridge" between your apps hasn't collapsed.

Let's explore testing in more detail.

How to test Micro-Frontends

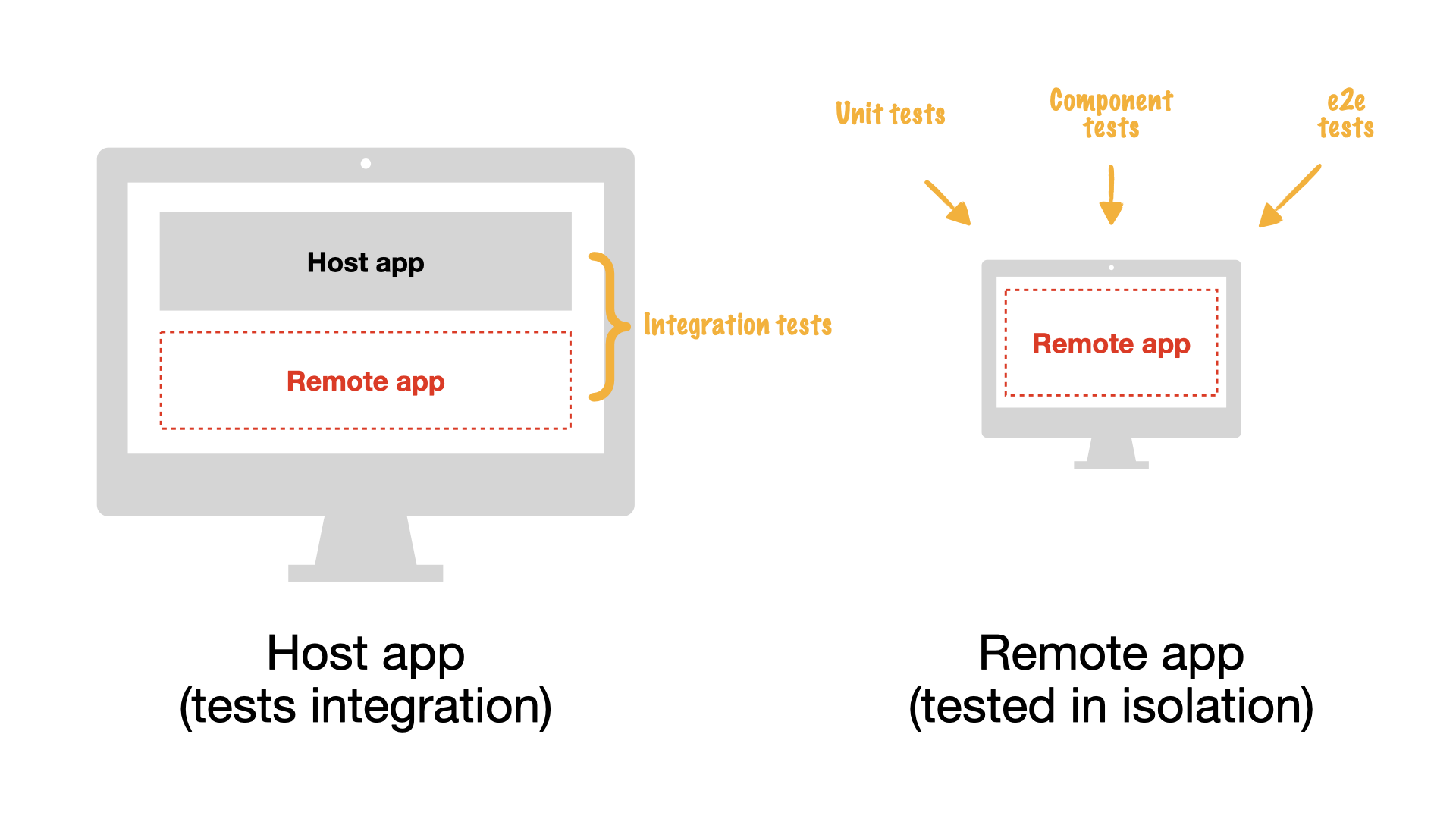

When you start working with Module Federation, there's an opportunity to revisit your testing strategy as you're now able to test your micro-frontends in full isolation. Unit and component tests are still the foundation of your testing strategy, but how you test user behaviour end-to-end becomes a whole new ball game.

- You can test the host and remote apps together from the host app's entry point, but you need to make sure the remote app's entry point is actually loaded and rendered, which may require some additional CI configuration updates.

- You can test the remote app in standalone mode, providing any host app dependencies, such as the API, as mocks. This is a great way to test the remote app's behaviour in isolation, but you need to make sure to test the remote app's behaviour in the context of the host app as well.

The latter is an interesting approach as it helps reveal any hidden dependencies or coupling between the remote and the host, thus enforcing modularity and encapsulation. Once you have resolved the interface between the two, you're basically more unconstrained in how you test the remote app as you don't need to worry about the host app's baggage anymore, which can significantly speed up how you write tests and maintain your testing pipeline.

Testing the remote app in standalone mode is a great way to improve modularity and encapsulation

However, it's not without its challenges: you need to make sure to test the remote app's behaviour in the context of the host app via integration tests, as illustrated in the image above.

Defining your strategy forward

Choosing to break away from a monolith is a significant architectural pivot. Before committing, your team needs to weigh the immediate "Developer Experience" gains against the long-term maintenance of a federated system.

The Pros (The Speed)

- 🌱 Greenfield Freedom: Total stack autonomy leads to vastly better DX.

- ⛓️💥 True Decoupling: Parallel feature development without merge-conflict hell.

- 🚀 Faster Shipping: Independent deployments mean you ship when you are ready.

The Cons (The Complexity)

- ⚙️ Config Overhead: Polyrepos lead to fragmented and duplicated tooling.

- 🧶 Dependency Debt: Tightly coupled monolith libraries are hard to extract.

- 📉 Learning Curve: Requires new expertise in federation and monorepo orchestration.

Important considerations

That said, Micro-frontends are probably more suitable for large organizations with multiple teams working on different parts of a large application. They solve organizational problems rather than technical ones.

Module Federation also does not eliminate the need for architecture — without governance, it may simply distribute the monolith's chaos and burden across repositories.

Before fully committing to Micro-Frontends, it's highly recommended to create a Proof of Concept to validate the concept and understand the potential challenges.

The Monorepo Multiplier

As we’ve discussed, the most effective way to mitigate the "Cons" is to embrace a monorepo strategy. Consolidating your modules under one roof allows you to deduplicate your TS, linting, and testing configurations. It transforms your shared UI and utility libraries into "local" packages that don't require a release cycle to update. Most importantly, it gives you a single, coherent view of your entire architecture in every Pull Request.

Two different approaches to Micro-Frontend architecture: polyrepo vs. monorepo

Just be aware of the architectural and maintenance challenges this involves. If your monolith doesn't yet yield insurmountable technical challenges, modularizing it first may achieve similar benefits with less complexity.

The Path to Decommissioning

Even with a brilliant new architecture, the legacy monolith will likely remain part of your stack for some time. While it might feel like dead weight, it’s helpful to view it through the lens of a gradual migration:

- 💰 Extraction by Value: Identify modules with high business value or frequent change requests. Extract these first, porting them to the new stack as federated remotes.

- 🗑️ Strategic Decommissioning: Use this transition to identify obsolete features. Don't port them; decommission them.

- 🌅 The "Sunset" Phase: As more features migrate to the federated model, the monolith naturally shrinks until it becomes a simple "legacy host" that can eventually be replaced entirely.

By treating the monolith as a temporary shell from which you transition to a new, modular architecture, you can modernize your stack without the risk of a "big bang" rewrite.

I hope this post has given you a good overview of the benefits of Micro-Frontends and Module Federation, and the challenges you may face when adopting them.

In a future post, I'm going to explore the monorepo architecture in more detail, how to setup it up with Module Federation, and a gradual migration strategy for distributed front-ends.